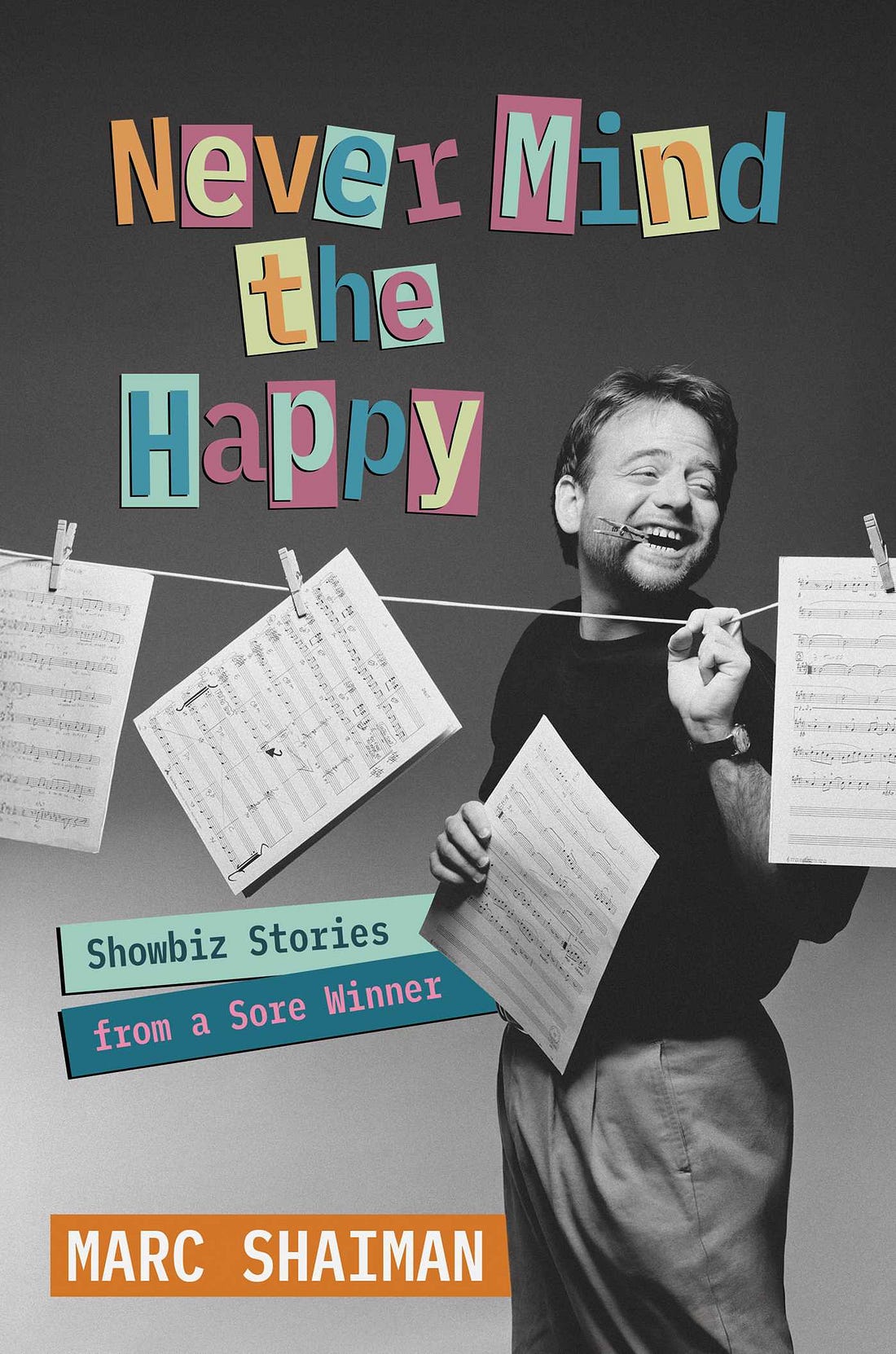

Songwriter Marc Shaiman vs. the ‘Unfair’ Oscars

Songwriter Marc Shaiman vs. the ‘Unfair’ OscarsBuckle in: The legendary composer & lyricist’s unfiltered take on Hollywood, his ‘nightmare’ Mike Myers film and the Academy’s ‘nasty’ original-song moveI cover where music & Hollywood meet. I interviewed Sara Bareilles about going through grief, spoke with Spike Lee about how he recruited Aiyana-Lee for Highest 2 Lowest and chatted with Amanda Seyfried & Daniel Blumberg about The Testament of Ann Lee. Reach me at rob@theankler.com“Leave it to showbiz to put you on a pedestal on Tuesday just to get a better shot at your balls on Thursday,” Marc Shaiman tells me. The famed composer and lyricist knows from whence he speaks. His résumé is the stuff of legend, filled with unbelievable highs — seven Oscar nominations, an Emmy win, co-creating the Broadway juggernaut Hairspray, scoring classics like When Harry Met Sally…, The American President and Sister Act, and, yes, orchestrating the First Wives Club finale where Goldie, Bette and Diane belt out “You Don’t Own Me.” And then, yes, the kicks in the balls. Getting his Team America score tossed. Being fired from Mike Myers’ chaotic The Cat in the Hat after declining to compose three different versions of the movie for three competing edits. Watching the Academy announce that only two songs would be performed at the 2019 Oscars — leaving his own nominee out in the cold. “Any profession is cutthroat, but I have only dealt with showbiz my whole life — so I can’t really compare it to a job in banking,” Shaiman says. “Hollywood just has more of a spotlight on it.” Shaiman, 66, a New Jersey native, has lived his entire adult life in the spotlight’s glare, often standing just close enough to the statue to feel its heat (but never win). If that proximity has made him anything, it’s that he’s honest. Brutally honest. About the Oscars. About collaborators. About flops. About grief. About the absurdity of an industry that can’t decide whether to canonize you or cut you loose. In his new memoir, Never Mind the Happy: Showbiz Stories from a Sore Winner, Shaiman, who began his career as a pianist and cabaret musical director, writes with the same candor he brings to conversation — equal parts showbiz gossip, self-laceration and genuine tenderness, especially when talking about longtime friend and collaborator Rob Reiner (A Few Good Men, When Harry Met Sally…, Misery and The American President). The book is not a victory lap. It’s more of a backstage pass to the victories that didn’t quite happen — and the resilience required to keep going anyway. When we spoke, he had plenty to say about the Academy’s latest original-song controversy, the year he dressed like a pimp at the Oscars, the projects that imploded and what AI might mean for the future of songwriting. He also had one recurring request when it comes to awards night: “I don’t care if we win,” he told me about one recent ceremony. “I just don’t wanna lose.” Read on. When you were an Oscar nominee in 2019 for “The Place Where Lost Things Go” from Mary Poppins Returns, the Academy decided against showcasing all five nominated songs on the live ceremony. They relented. This year, it’s happening all over again. What do you make of that? At the time, I was lucky to know Bradley Cooper and Kevin Feige well enough to have their email addresses, since they were the producers of the two movies whose songs were being performed (“Shallow” from A Star Is Born and “All the Stars” from Black Panther). So I reached out to them and said, “You know, this is kind of unfair,” and they agreed. The Academy couldn’t undo what they’ve already done, which had already cast a weird light on the other songs, as if they were not worthy. It was just a nasty thing to do. I never queried Bradley or Kevin about who they spoke to, but two days later, it was announced that all five songs would be performed on the show.  This year, only “Golden” from KPop Demon Hunters and “I Lied to You” from Sinners will be performed live during the ceremony. Doesn’t that imply a bias if they’re choosing what contenders to feature? Yes, of course. You’ve gotten seven Oscar nominations, and I hate to break it to you, but you never won. If you had to choose one year when you should have won, what would it be? I would say 2000, the year of the South Park: Bigger, Longer and Uncut song “Blame Canada.” I thought enough people loved the movie, loved South Park and loved the idea that a song from a South Park movie was nominated for an Oscar. I thought there could be enough of a groundswell there (Phil Collins’ “You’ll Be in My Heart” from Tarzan won). Another one is the score for The American President (which lost to Pocahontas at the 1996 ceremony). But I knew we weren’t going to win for our Mary Poppins Returns song, because we were up against Lady Gaga. On the red carpet, I said, “They’re going to shove that Oscar so far up her ass that when she smiles, it’ll look like a filling!”  What’s the mood at the ceremony usually like for a nominee? It’s like a witch’s brew of every emotion you can feel, especially in those final seconds when your nomination comes up. Like at the Emmy Awards. I won one in 1989, lost around 15 in between, so at the most recent nomination for Only Murders In The Building, I turned to Scott Wittman and said, “I don’t care if we win… I just don’t wanna lose!” And how do you compare the performances? It’s just insane. The year South Park lost, Trey Parker said, “Well, let’s get out of here.” Who knew you could leave! But the best event is the Nominee Luncheon, because everyone’s equal there, and you get to know everyone. That was the year you dressed as a pimp, and Trey Parker and Matt Stone were wearing Jennifer Lopez’s and Gwyneth Paltrow’s iconic dresses. Was that the most surreal year for you? “The most surreal Oscars” doesn’t do it justice. All the others were just kind of… normal. I only found out the day before what Matt and Trey were doing, so I spoke to a great woman named L’Wren Scott, who had been hired that year to be the fashion coordinator of the Oscars, I guess, in case people needed help or ideas about what they were gonna wear. I’m not sure whether they’ve done it before or since. But thank God she was there because I said, “I can’t just be in a tux. What am I gonna do to make it seem like I’m not the odd man out here?” She threw together this sort of pimp-like outfit. The guys were also on acid, which I only found out when I got in the car with them after I had finished with the rehearsal. There’s nobody like them. The word genius gets thrown around a lot, but Trey Parker is a genius; he can just do everything, yet he is so collaborative, with such a sweet, warm heart. He’s really an anomaly. You’re known for a ton of original musical moments at the Oscars. For example, what was the inspiration for the numbers where Billy Crystal would famously sing, “It’s a wonderful night for the Oscars. Oscar, Oscar!” Back in the day, the show would often open with a cheeseball medley. Billy, the writers, and I were like, “How can we poke fun at the kind of musical numbers the Oscars used to have, and yet hopefully make them entertaining?” So, that was a tightrope we walked every year, not wanting to become the cheesy medley ourselves. One year at the Oscars, a very far-right Christian guy came out and said that SpongeBob was gay. Robin Williams and his manager, David Steinberg, called Scott and me and suggested we write a song about what he suspected about the other animated characters. We wrote it, but the censor kept saying, “You can’t say this. You can’t say that.” We kept changing it, but eventually we couldn’t keep rewriting it, so we pulled the song.  You’re candid in the book with stories about working with everybody from Scott Rudin to Barbra Streisand. Was there anything you decided to remove because it was too personal? And if so, would you like to tell them here? Laughs I don’t think I wrote anything that’s a real gut punch. I’m mostly punching myself in the gut. One thing I softened is when I talk about Smash. I eliminated some of the stories about working on the TV show because, as I was writing, the Broadway show flopped. It was like, enough already! You don’t shy away from your flops in the book. I left out a million. I couldn’t talk about every project I’ve ever worked on. I wrote about being dropped from Team America; they didn’t use the score I wrote. That was a disappointment after such a wonderful experience with the South Park movie. But that one represents, I’d say, three instances of me having a score thrown out. I totally left out the entire story of working on The Cat in the Hat with Mike Myers, which was a nightmare from beginning to end. After they filmed the movie, I got a call that Mike had his own editing room, the editor had his own editing room and the director — the sweetest guy on Earth, named Bo Welch — also had his own editing room. The three of them were editing the movie in different ways, and Mike asked me to write the score for all three versions. I said, “No, I was hired to write one score. You guys figure it out.” And he had me fired. But it was a relief; getting fired was no problem. And they paid me my full fee! I wrote a telegram to the head of the music department saying, “Thank you for your graciousness. Feel free to fire me from any other future Universal project!” My favorite two-word phrases in the English language are “children’s menu,” “comments disabled” and “kill fee.”  I want to ask you about Rob Reiner and his wife, Michele. How have you been grappling with that tragedy, which sadly coincided with the release of the book where you detail your close friendship and collaboration? When I first started doing press, it was literally right after that happened, so it was hard to even speak of it — even though I would and will gladly talk about Rob Reiner for the rest of my life. But getting to talk about him has been cathartic. As I write in the book, I’ve had a lot of loss in my life, so I am very familiar with grief. But what happened with Rob and Michele is so hard to believe that I haven’t really grieved it completely. And I wonder, will I ever? The night after it happened, I flew out to Los Angeles to join a certain group of my friends in the comedic community and we sat shiva, and I certainly shed tears that night. Afterwards, I was numb. A few weeks later, the New York Times came to my apartment to shoot a video and asked me to play my theme from The American President, which Rob directed. As I was playing, I was filled with memories of working with him. When I got to the final chord, the finality hit, and, well, it all came out, in front of all these strangers from the video crew. They got to witness my first real expulsion of grief, where I just couldn’t stop sobbing; I couldn’t catch my breath. But it felt good, as if it were step one. But here I am talking to you about him, and I don’t even have a lump in my throat. Because the truth is, I still just can’t believe it. What also helped was this nationwide feeling. Everyone felt they knew him, and he actually was the person they felt they knew.  Before we go, I wanted to ask about AI and how you view its impact as a creative person in Hollywood. It’s here to stay, and it will change everything. Humans will still create, but AI will go on, with or without humans. I have now heard numerous things that I cannot believe. It’s imperceptible. You would never know that any of this was not all created by a human. Someone sent me an AI-generated birthday song, supposedly in the style of Marc Shaiman. I wasn’t exactly flattered by what AI thought, but I understood its choices. When Scott and I were writing with Benj Pasek and Justin Paul for the Tony Awards, when Cynthia Erivo hosted, just for fun, we asked AI, “What would lyrics for a song written by the four of us be like?” We didn’t, of course, use any of it, but its ideas weren’t that terrible. I don’t know that songwriting and writing for theater could ever be bested by AI over human beings in a room. But with things like film scores and music libraries, you could have 10 minutes worth of music within a second. That may be true, but AI could have never thought of something like the South Park movie scene where you created Terrance and Philip’s farting-tap dance break. I would imagine or hope that the idea of having a fart tap-dance break was something that would have to come from a deranged human. Follow us: Got a tip or story pitch? Email tips@theankler.com ICYMI from The AnklerThe Wakeup PSKY passes DOJ hurdle as Senate perks up The WGA Files & the $80,000 Business Card Richard Rushfield peeks inside the disclosures; plus: the new new Colbert mess Tubi’s Gen Z Grab in the U.K. Heats Up Its Creators program heads to Britain as its GM explains strategy — and the HBO Max threat — to Manori Ravindran The Three Budget Buckets Running TV in 2026 Lesley Goldberg unpacks a quiet financial reset now determines who gets an order and who gets cut Gen Z Will Make or Break These 7 Upcoming IP Films Matthew Frank reports on the divide between loser legacy brands and lived-in fandom The Billion-Dollar Scramble for Wasserman Ashley Cullins on the chatter as private equity, rival agencies and power players size up the company’s worth The Goldfish Rules Richard’s 26 principles for marketing in the zero-attention age The Man Who Built Marty Supreme (and Won Over Chalamet) Katey Rich talks to Jack Fisk about a career working with Iñárritu, de Palma & Malick 🎧 Hollywood Is Back on Strike Watch 🎧 From Us Weekly to City Hall? Spencer Pratt Makes His Case to Janice Min — Again 🎧 Ryan Coogler Wrote Sinners for Wunmi Mosaku — She Just Didn’t Know It MORE FROM ANKLER MEDIANew from Natalie Jarvey’s creator economy newsletter: Video Pods Are Eating TV. Apple Wants In Andy Lewis’ latest IP picks: Two Summer Beach Reads Ready to Become Popcorn Thrillers on the Screen |